10 October, 2013: Questions to the Department of Children and Youth Affairs, for answer before the meeting of the Committee on Health and Children.

Question 9: U.N Committee on the rights of the Child report.

Question 10: Special Rapporteur on Child Protection Reports

Question 11 Youth work budget.

Question 9: U.N Committee on the rights of the Child report.

On 16 July 2013, Minister Fitzgerald advised that her Department had finalised and submitted to Government for approval Ireland’s consolidated Third and Fourth State Report to the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child. The submission of this Report, which is already considerably overdue (April 2009), are essential components of Ireland’s international obligation in relation to the review and monitoring process of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC). Can the Minister provide a definitive answer as to when Government approval will be secured and when the consolidated Reports will be furnished to the UN Committee?

The Government approved a consolidated 3rd and 4th Report in July 2013 and the report was submitted to the on the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child, in August 2013. The report is available on www.dcya.ie and outlines the most significant developments for children and how Ireland has been implementing the main aims of the UN Convention during the period 2006 to 2011 inclusive.

Ireland ratified the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child in 1992. Ireland submitted our second progress report to the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child in 2005. Following the establishment of the Department of Children and Youth Affairs in June 2011, I directed that a substantial progress report, combining the 3rd and 4th reports, to cover the period 2006 to 2011 inclusive should be submitted to the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child. An Inter-Departmental Liaison Group was established to prepare the report and a draft of the report was completed in December 2012. This draft report formed the basis of consultations with the NGO sector and subsequently the Children’s Rights Alliance, on behalf of the NGO sector, submitted its observations on the draft to the Department of Children and Youth Affairs. These observations were considered by my Department in conjunction with other Departments and a draft report prepared for consideration by Government.

With the Report’s submission now complete I look forward to attending a hearing of the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child on the report, although the timing of the hearing will be a matter for the UN Committee. I understand there is currently a backlog of hearings to be dealt with by the Committee. The hearing when it takes place will provide an opportunity to further bring the Committee up to date on what we have achieved as part of the programme of this Government since 2011.

Question 10: Special Rapporteur on Child Protection Reports

There have been a number of important Reports concerning children over the last number of years. Significant amongst them are the Fifth and Sixth Reports of the Special Rapporteur on Child Protection, Dr Geoffrey Shannon. In each of these Reports, recommendations are outlined to Government to improve the experiences and lives of children in Ireland. In the interests of transparency and accountability, and indeed to facilitate the tracking of said recommendations, will the Minister consider adopting a formal response to the recommendations similar to Ireland’s response to the Working Group Report on the Universal Periodic Review, whereby indication is given to each recommendation as follows: examined and supported; to be examined and responded to in due time; not supported? And, will the Minister ensure that implementation mechanisms and timelines are developed and published as part of the formal response to each Report’s recommendations?

There have been a number of important reports concerning children published over the last number of years, among them are the reports of the Special Rapporteur on Child Protection and, significantly, the report of the Commission to Inquire into Child Abuse (referred to as the Ryan Report) published in May 2009. Currently the monitoring mechanisms vary between no formal mechanism, once off responses or annual monitoring.

The Special Rapporteur on Child Protection is appointed by the Government and his recommendations are relevant to a number of Government Departments and Agencies. The reports of the Child Protection Rapporteur are circulated to all relevant Departments and it is a matter for individual Departments to take the appropriate action on any recommendation relevant to its work. Where recommendations are proper to the DCYA they form part of the process of policy development and, if appropriate, are incorporated within the Department’s business planning process.

The most formal response to a report is that of the Implementation Plan in response to the Ryan Commission Report, which was published in July 2009. The Plan sets out a series of 99 actions to address the recommendations in the Ryan Report, and includes additional proposals considered essential to further improve services to children in care, in detention and at risk. The Government committed to implementation of the Plan. The 99 actions identified in the Implementation Plan are the responsibility of a number of Government Departments and Agencies. I, as Minister for Children and Youth Affairs, have had the responsibility for overseeing the implementation of the actions set out in the plan. I chair a high level monitoring group with representation from the Department of Education and Skills, the Irish Youth Justice Service, the HSE, the Gardaí, the Children’s Rights Alliance and my Department. Three Progress Reports have been published so far and the final Progress Report is due at the end of this year.

My Department is currently preparing a monitoring framework for higher level oversight of recommendations from all significant child care reports, which is intended to be put in place following the completion of the formal monitoring process for the Ryan Commission Implementation Plan. In this regard the intention is to review current monitoring and reporting mechanisms, with a view to capturing all relevant recommendations and streamlining progress reporting, to provide effective and sustained implementation of recommendations.

My Department has also commissioned independent research on the extent to which previous reports have influenced policy and practice. This research also identifies learning as to how to improve the influence and usefulness of recommendations made in such reports. It is my intention to publish this research as I believe it will be of general interest and particularly useful to anyone engaged in conducting reviews or investigations in the future.

Question 11 Youth work budget.

To ask the Minister for Children and Youth Affairs to share with the Committee the discussions her Department had with the Department of Public Expenditure and Reform concerning the budget for youth work in the next round of the Comprehensive Review of Expenditure from 2015-2017. Did the Minster emphasise the disproportionate cuts to youth work in the overall budget adjustments for her Department in the last round from 2012-2014, and also will the Minister give details of when youth work organisations will receive details of funding for 2014 following the budget on October 15th?

Officials of my Department have met with representatives of all the national organisations that are funded under the Youth Service Grant Scheme to share information and to hear from the organisations about the impact of the reductions in funding on the services that they provide. I have met with and continue to meet with, many youth projects and groups to try and see how we can work together to minimise the impact of these necessary savings in order to ensure that the provision of quality youth services to young people is sustained in these challenging times.

Funding requirements and how resources should be prioritised and allocated across each area of Government spending are generally considered as part of the annual estimates cycle and budgetary process. I am sure the Senator will appreciate that it would be inappropriate for me to comment at this time on any decisions that may be taken by Government in the context of Budget 2014. The Committee can be assured that the benefits of youth work have been fully considered as part of my Department’s input to Budget 2014. As soon as Budgetary figures are available my Department will assess the implications for youth funding and engage with the sector in planning the approach to 2014. It would be my hope that the earlier timing of the Budget will allow for the notification of allocations to be brought forward so that they can take place prior to the commencement of the year.

An Update on Youth Justice Policy

28 January 2014

I have a good deal to say but I will try to contain myself.

I welcome the Minister, who has laid down a comprehensive statement on youth policy, which she had hoped to do in December. It is great that this is all together and that the Minister used the House to do this. The Minister mentioned that we are improving our data, but I remain concerned at the lack of data in the area, a point to which I will return. This particularly applies to juvenile offenders and children coming into contact with the criminal justice system. Through an analysis of various reports compiled by the Association for Criminal Justice Research and Development and a number of significant academic studies by the likes of Sinead McPhillips, Dr. Ursula Kilkelly and Dr. Jennifer Hayes, three key risk factors associated with children who became involved in criminal behaviour have been identified. As the Minister knows, these are family background, educational disadvantage characterised by poor literacy skills and low levels of academic achievement, and personal and familial factors such as alcohol and drug misuse, intergenerational crime and mental health problems. The studies have categorised the factors for us but it is not the understanding of the majority of the public, who are confronted daily with media reports and headlines about violent youth offenders and delinquent youths who are out of control. In the absence of political and media discourse to the contrary, it is understandable that they want to see zero tolerance and tough-on-crime type approaches. That is why the Minister’s intervention is important. I support her understanding and her moves to promote prevention and early intervention.

I commend the work of so many of the agencies involved in the delivery of juvenile justice policy in Ireland, such as An Garda Síochána, particularly its Garda youth diversion projects, the dedicated young persons’ probation division of the Probation Service, the Courts Service, and the Irish Prison Service, as long as it still has 17-year-old children detained in St. Patrick’s Institution. I would like to make special mention of the Irish Youth Justice Service, IYJS, which has been leading and driving reform in the area of youth justice since its creation in 2005. It has made important strides and shows the importance of Departments working together, as the Minister outlined.

It is a real missed opportunity that a centralised data and research department has not been established in the IYJS. We need to co-ordinate inter-agency research between the agencies involved in the delivery of juvenile justice and map the trajectory of the child through the criminal justice system. Every child has an individual story but we mostly get to read these in child death reports and other significant reports. We need to collect the data earlier. We also need to identify divergences between the policy and legal framework of youth justice and its implementation, administration and practice.

I would like to personally congratulate the Minister on a number of successes and advances in youth justice policy under her stewardship. In particular, I welcome the decision on St. Patrick’s Institution and today’s update on bringing the detention centres together. It has been long promised, but the Minister has done it and I thank her for it. We need a unified approach and I am happy to hear that a new head of the campus has been appointed. I look forward to the opportunity to support the legislation brought to the House. There are significant challenges in respect of the campus but I will support the Minister. In the interim, since December 2013, 17 year olds are being remanded to Wheatfield Prison. I note specific concerns raised by the Irish Penal Reform Trust in respect of 18 to 21 year olds, and obviously any 17 year olds detained there, that Wheatfield is often overcrowded and does not have adequate education and training capacity for its inmates. The focus for our young adult prison population must be on rehabilitation and not simply containment. I remain concerned about the interim period and how we are serving these young people.

I raise my concern over the lack of sufficient special care and protection places available to children with severe emotional and behavioural difficulties. I raised the point in November when we debated the Child and Family Agency Bill. From a juvenile justice policy perspective, my concern echoes that articulated by Judge Ann Ryan, who until recently presided over the Children’s Court in Smithfield. She has spoken of her frustration at the lack of HSE special care and protection places available to children, citing a correlation between the failure of the State to appropriately deal with these acutely vulnerable children and the likelihood that many will find themselves before the children’s courts facing criminal charges.

I remain concerned about this. For example, a HIQA report was published and the response was to close the centre, yet there are not enough places for the children who are vulnerable.

I refer to children who are remanded in custody. The most recent data available from the IYJS are from 2008 and show that of the 111 children detained on remand in children detention schools, only 44% went on to be sentenced to detention on conviction. That raises a twofold concern – first, that detention as a last resort requirement, the principle underlying the Children Act, was not being adequately embraced by judges at the pre-trial stage and, second, that there was an urgent need to introduce a formal system of bail support to help children to manage their bail conditions, thus helping to reduce the number being placed in detention on remand. Unfortunately, the pilot scheme mooted in 2008 in Young People on Remand: The National Children’s Research Strategy Series to offer bail support services for vulnerable children who ceme before the Children Court in Dublin and Limerick failed to materialise owing to insufficient resources. Will the Minister provide the House with the figures in this regard for the past few years? I would be interested in seeing and trying to understand them. I fear the position has not improved much from what I hear anecdotally. Will the Minister consider revisiting the bail support pilot scheme?

I refer to the issue of training. Staff and personnel engaged in the formulation and delivery of youth justice policy should be trained in the provisions of the Children Act. The Committee on the Rights of the Child made a recommendation to this effect in 2006. An advanced diploma in juvenile justice is being run by the King’s Inns. The course is attended by a great mix of professionals from a wide variety of disciplinary backgrounds, including legal professionals, juvenile liaison officers, prison officers, detention centre staff and the IYJS. Robust, specialist training such as this needs to be rolled out on a systematic basis and attendance supported by employers such as the State.

I also raise the issue of the age of criminal responsibility. The concluding observations of the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child expressed concern about the age of criminal responsibility being ten years under the Criminal Justice Act 2006. The Minister has submitted a consolidated report to the committee. Has she had a communication from the committee? Will Ireland consider this issue before it appears before the committee?

On Second Stage of the Courts and Civil Law (Miscellaneous Provisions) Bill in March last year I alerted the Minister for Justice and Equality to my concern about routine breaches of the Children Act in the Dublin Children Court. Examples include the court appointed registrar calling the name of the child in the public waiting room, the former practice of District Courts including YP, meaning “young person”, beside the child’s name on the court list and the presence of Gardaí and legal representatives unrelated to the specific case in the court which is mandated to sit in camera. The Minister said he would write to the Courts Service and I await a response. I raise the issue in this debate because we need to consider practical remedies to ensure the Children Act is implemented in the spirit intended by the then Minister and the Houses of the Oireachtas.

Child and Family Agency Bill, 2013, Second Stage.

Wednesday 27 November 2013

http://www.kildarestreet.com/sendebates/?id=2013-11-27a.75#g85

The Minister is, as always, very welcome to the House, especially so given her introduction of the Bill before us. It provides us with immense potential to streamline and co-ordinate services for children. It is a huge and impressive undertaking involving three source agencies – the HSE, the Family Support Agency and the National Educational Welfare Board. I see the evidence and appreciate the seriously hard work that has been done by the Minister personally and her departmental officials. I thank Liz Canavan, assistant secretary at the Department, for a thorough briefing on the Bill yesterday afternoon and also the Minister for her clarification at the briefing.

I fully agree that what we are striving for now is to get the agency operational by 1 January 2014, the establishment date. In that vein, I wish to be very clear that I am approaching this Bill in as supportive and constructive a manner as possible. Any issues I raise are in the context of the fact that we are all striving to produce the best possible agency. I will do everything I can to ensure the Bill’s passage through this House.

I followed closely the Bill’s passage through the Dáil. I acknowledge and welcome the fact that the Minister has made significant changes to the Bill, in particular following suggestions from civil society organisations such as the Children’s Rights Alliance and Barnardos primarily. We have a unique opportunity to ditch ineffective systems and to finally make sure that children get the treatment they deserve, and that families get the supports they require also. I am concerned about the emphasis on management and the centralisation of services. I understand it in part but I fear the creation of a bureaucracy. What we want to do is ensure consistent standards throughout the country. An effective and accountable child and family agency will be a monumental step forward for a country that has so spectacularly failed some of the most vulnerable children in the past.

We must ensure consistency and standardised practice on the ground. This opportunity has been a long time coming. I thank the Minister for bringing it to fruition. We know that history is unforgiving. As the Minister outlined, there have been more than 30 reports. We must learn from our failings and demonstrate clearly that is the case. We are duty bound to get this right and everyone is striving for the best outcome for children. I will submit a number of amendments on Committee Stage and Report Stage in an effort to strengthen the Bill before us today. I will make every effort to ensure the Bill’s passage through the House. I look forward to a fruitful debate.

I commend the Minister on her role in securing Government approval of a proposal to strengthen legislation on aftercare, by introducing a statutory right to an aftercare plan. This will be done by way of an amendment to the Child Care Act 1991 and is an essential component to ensure stability in care and to enable young people to make the transition from care to independence in a safe, progressive, tailored and appropriate way. The Minister may be assured of our support when she brings this landmark legislation through the House.

At this juncture I want to focus on how we can ensure that we give the new agency the best start possible and restore public confidence in our child and family services. The Minister mentioned the referendum on children and when I travelled around the country, the biggest concern related to how people had been treated in the past by the agencies or how they perceived they would be treated. These perceptions are significant with regard to how people feel and we should not diminish those feelings. It is important we find ways to instil confidence in this new opportunity we are discussing today.

We heard in the news today about the potential overrun in the HSE. I will not get into a debate on that, but it gives rise to more concerns about the resources that will be transferred from the current HSE operations to the Child and Family Agency. Can we guarantee there will be enough of a budget transfer to do what is planned today? Can we guarantee there will be no loss of services? What improvements can we expect? I am concerned the agency may start with a deficit. That would be like a ball and chain being added on the starting line. I fear that the transfer of resources may mean the transfer of a deficit. This would be totally unacceptable. We have an opportunity with this new agency and we need to use it. During Committee Stage, I will look more closely at the details of the budget for the agency, particularly with regard to outsourcing. We know the agency has a budget of approximately €545 million, and I understand €100 million of that will go to outsourcing. I will seek further clarity on that on Committee Stage.

The issue I want to focus on today is the issue of special care. The issues in this regard are indicative of some of the issues I am raising about confidence and how we go forward. Under the special care order of the Child Care Amendment Act 2011, only children and young people aged from 11 to 17 with serious emotional and behavioural difficulties that put them “at a real and substantive risk to his or her health, safety, development or welfare” and who are unlikely to receive special care or protection “unless the court makes such an order” can access these facilities. An example of this may be a child who is self-harming, suicidal, abusing drugs and-or alcohol, where all other attempts by the Health Services Executive have not stabilised the current, serious situation. Rightly, one has to go to the High Court to obtain such an order. This is an appropriate safeguard due to the nature and seriousness of such intervention and the restriction of the individual’s liberty.

The recent report by the HIQA into Rath na nÓg raised serious concerns. The response from the HSE was to close the facility, which was relativity new. One could be forgiven for thinking as a result of that action that there is no demand for places. However, I understand there are currently 16 children on a waiting list for places and as many as 40 children who have not got onto the waiting list in need of a special care placement. Having read the definition, I cannot understand how there can be a waiting list for special care.

I am conscious that we are sending children to facilities abroad. For this to be done legally involves a time limit. Therefore, this involves returning to the High Court time and again to extend the period. The State is paying substantial costs both legally and for the provision of these places outside the State. Can we not develop a home grown solution that will be in the best interests of children? I am also concerned about the current arrangements around applications and placement for special care. The personnel in the HSE who decide whether to initiate a High Court application for special care are the same personnel who manage the number of special care places that are available. This is a serious concern because of the implicit conflict. Somebody said to me that the philosophy is: “If we do not have a place, we do not make an application in the first place.” Surely need and the best interests of the child should be the driving and deciding factor in whether a special care order is sought. Are we failing children today? Are we failing the 16 children on the waiting list? They have been assessed and identified as needing special care. At the least, I ask for the Minister’s assurance that this practice, as outlined, will not carry over into the new agency. There should not be a waiting list for special care.

The Minister was right to say we need to look at co-operation and bringing services together. I agree we must break down the barriers between agencies and services. We need an informed and integrated approach and for all of them to be under one roof. One of the regrets I have as we move forward with this is that children with disabilities will not be under the roof of the agency. Public health nurses will not be included either. All too often we hear that public health nurses are identifying upstream issues relating to a young child. At a recent meeting of the Oireachtas Joint Committee on Health and Children, the special rapporteur on child protection gave us what could be called a master class on children’s rights. One of the issues he raised was the issue of alcohol as a risk indicator and the need for social workers to consider this.

The issue now is how are all of these other services to communicate and liaise with the new agency. We have talked about integration and working together. Let us look for example at the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services, CAMHS. We would assume, judging by its name, that this service would transfer to the new agency. CAMHS caters for young people up to 16 years, with an extension on occasion to 18 years. Social workers on the ground say they find it extremely difficult to access CAMHS, particularly once a child has been put into care. It is almost as if the perception is that once they are in State care, the State cannot outsource the facilities to CAMHS and will deal with them in the community. This is a further cost on the State. There is a concern that if CAMHS does not transfer to the new agency, this will further exacerbate the difficulty social workers are experiencing accessing these services for children. We have seen in the child death report the critical role that CAMHS plays. I do not understand why it is not being made part of the new agency. Is it because it does not want to be? This is a serious concern.

There is plenty more I could say, but I will keep it for Committee Stage. I am anxious to ensure the agency will be about all children and child welfare and that its remit is not limited. I do not question the Minister’s commitment, but the Bill is about outlining and putting down a foundation for the future. It is about a future when none of us will be here. We need to grasp the opportunity we have and maximise the potential of the Bill.

Link to Committee Stage: http://www.kildarestreet.com/sendebates/?id=2013-12-03a.189#g193

Links to Report Stage: http://www.kildarestreet.com/sendebates/?id=2013-12-05a.101#g110

Independent Group Motion: Asylum Seekers and Direct Provision

Wednesday 23 October 2013

For full debate please see http://www.kildarestreet.com/sendebates/?id=2013-10-23a.178#g180

Senator Jillian van Turnhout

“That Seanad Éireann –

notes the calls from civil society organisations, legal practitioners, academics, human rights activists and Members of the Oireachtas for reform of Direct Provision, the administrative system for accommodating asylum seekers;

notes that, according to the latest available statistics from the Reception and Integration Agency (RIA) Monthly Report June, 2013, there are 4,624 RIA residents ‘live on the system’ of whom 1,732 are children;

welcomes the commitment by the Minister for Children and Youth Affairs to meet with the Seanad Cross Party Group on Direct Provision, made at the meeting of the Joint Committee on Health and Children on 10 October, 2013; and

calls on the Minister for Justice and Equality to –

– outline his response to the recommendations of the Government’s Special Rapporteur on Child Protection, Dr. Geoffrey Shannon, in the Fifth Report (July 2012) for

– an examination to establish whether the system of Direct Provision itself is detrimental to the welfare and development of children and whether, if appropriate, an alternative form of support and accommodation could be adopted which is more suitable for families and particularly children; and

– the establishment in the interim of an independent complaints mechanism and independent inspections of Direct Provision centres and give consideration to these being undertaken through either HIQA (inspections) or the Ombudsman for Children (complaints);

– outline the legislative basis for payments to asylum seekers in direct provision accommodation and the effect on these payments, if any, of the Social Welfare and Pensions (No. 2) Act 2009 which precludes asylum seekers from being granted habitual residency status; and

– further to the Minister’s announcement in January, 2013 that ‘[r]eform of the immigration system will be sustained in 2013 and I will be focusing on major

legislative and procedural measures such as the Immigration, Residence and Protection Bill’, to debate with Members of Seanad Éireann how best to reform Ireland’s reception and asylum system.”.

I thank everyone who has signed and supported this motion, particularly my Independent group colleagues for allowing group time to be used. I wish to acknowledge the years the Minister spent as the Opposition spokesperson for children. He demonstrated a real understanding and commitment to the promotion and protection of children’s rights in Ireland and I am confident it has been continued under his remit as Minister for Justice and Equality.

I welcome the Minister’s commitment to re-publish in revised form the Immigration, Residency and Protection Bill, which is currently stalled on Committee Stage in the other House and which has been eight years in production.

I welcome this opportunity to have an open and frank discussion about the direct provision and dispersal system and to make suggestions for its reform process. This is a sensitive societal issue and I appreciate that the Government has decided not to table a counter-motion, thus allowing the debate to continue in a constructive and inclusive manner. All too often we perpetuate a political environment where Government concedes little for fear of exposing itself to liability. I wish this were not the case but I understand that it is. My hope is that the Minister and the relevant Departments are listening to what we are saying in a spirit of constructive engagement. We are all striving to make the society in which we live a better place for all who live in it. I also note that a root and branch challenge of the direct provision system taken by three families, has been given leave to proceed by Mr. Justice Colm MacEochaidh in the High Court yesterday.

It is very important that we as parliamentarians and legislators take ownership of the need to reform the currentdirect provision system rather than waiting and being forced into it by judicial imperative.

My entry point into the issue of direct provision is from a children’s rights perspective. This perspective has been informed by my work on related issues as the former chief executive of the Children’s Rights Alliance; the recommendations of the Government-appointed special rapporteur on child protection, Dr. Geoffrey Shannon; and the concerns raised by advocacy groups. On that note I welcome to the Gallery for this debate Sharon Waters from the Irish Refugee Council and Lassane Ouedraogo and Reuben Hamakachere who have personal experience of the direct provision system and actively campaign to bring about its end. I also welcome the media coverage of the issue and in this regard I would like to commend the Mary Raftery Journalism Fund, set up to advance ethical investigative media coverage of three key issues – mental health; immigrant rights and integration; and children and young people’s rights. It has recently funded Tom Mooney, editor of the Wexford Echo, and his series “The Children of Operation Hyphen”, which included an article on the state of mental health of people in direct provision. The Minister facilitated my own recent visits to two direct provision asylum accommodation centres, with my colleagues Senators Fiach Mac Conghail and Katherine Zappone.

It has taken me a long time to wade through the mire that is the political discourse on direct provision. It has been difficult to establish which features of the system belong to the Minister’s remit, the remit of the Department of Children and Youth Affairs or that of the Department of Social Protection. I have struggled to understand the distinction drawn between children “cared for by the State”, as is used to describe children in direct provision, and children “in the care of the State”. I have argued strenuously that children are children, irrespective of status, and that it is a stretch in credulity to claim that children in direct provision are in the care of their parents in circumstances where the parents’ autonomy to make even basic decisions about their children’s care – for example what and when to eat – is so limited as to render it absent. This is a concern shared by the Government’s special rapporteur on child protection, Dr. Geoffrey Shannon, which I will refer to again later.

My overwhelming concern is that the administrative system of direct provision, which has been operating in Ireland since April 2000, is detrimental to the welfare and development of asylum seekers, and in particular the 1,732 children currently residing in direct provision accommodation centres throughout Ireland. I am also very concerned that between 2000 and 2010, the direct provision and dispersal system has cost the State an estimated €655 million in contracts to private companies which are operating the centres on a for-profit basis.

In a recent letter to me as part of ongoing correspondences between our offices on direct provision, the Minister stated that the current system allows the State to provide a roof over the head of those seeking asylum in a manner that facilitates resources being used economically in circumstances where the State is in financial difficulty. I am not convinced the current system is the most economical and my colleagues, Senators Trevor Ó Clochartaigh and Martin Conway, will elaborate on alternative models and cheaper options. Furthermore, the best interests of persons seeking asylum should outweigh financial considerations in the discharge of our international, regional and humanitarian obligations.

In my time as a Senator, I have identified and spoken on the Adjournment about a plethora of difficulties, including the dubious legality of the direct provision system, the lack of an independent complaints mechanism for residents, the absence of independent inspections of direct provision centres where children reside, the decision by Ireland to opt out of the EU directive to allow asylum seekers to enter the work force if their application has not been processed after one year, the fact that there are no prospects for post-secondary education for young asylum seekers, which is like hitting a pause button for an uncertain and doubtlessly lengthy period of time, the fettering arid erosion of normal family dynamics and functioning and the lack of autonomous decision making. I do not intend to elaborate on each of these concerns but I will say a few words about the lack of specific legislation underpinning the provision of direct provision.

I know the Minister is aware of this specific concern as we have corresponded in its regard. I note in the same letter I mentioned previously what I took to be a suggestion that since existing laws – and although it is unspecified in the letter I presume social welfare law would be a good example – would “otherwise specifically prohibit asylum seekers from being able to be provided with the basic necessities of life”, we should simply ignore said provisions and carry on regardless. I fully accept and welcome that Ireland has an obligation under international and European human rights law to meet the needs of asylum seekers while their application for refugee, subsidiary protection or leave to remain is being considered. However, this must be done in a manner that complies with our own domestic legislation.

Direct provision was introduced in a haphazard manner in 1999 and 2000, with little concern for its relationship with Irish social welfare law. For several years, direct provision was viewed as part of the supplementary welfare allowance system, and this is evidenced from extensive documentation obtained by Dr. Liam Thornton under freedom of information and which I have furnished to the Minister in previous correspondence. Concerns were expressed by officials in the Department of Social Protection that the payment of €19.10 per week per adult and €9.60 per week per child was ultra vires, and the payment advice slips to asylum seekers continue to view the entirety of the direct provision system as being closely aligned with the system of supplementary welfare allowance, with deductions for accommodation, as administered by the Reception and Integration Agency, RIA. As the Minister is aware, supplementary welfare allowance can be provided in cash or in kind, and it appears that RIA, the Department of Social Protection and the Department of Justice and Equality had until recently considered supplementary welfare allowance as the legal basis for direct provision. To state that this scheme is wholly administrative, or that the Departments of Justice and Equality or Social Protection can act since the introduction of the Social Welfare and Pensions (No. 2) Act in 2009 contrary to legislation that debars asylum seekers from receiving supplementary welfare allowance displays a worrying approach of both Departments, which seem to consider that law does not apply to them.

Ultimate the failing of direct provision is the length of time asylum seekers remain in the system waiting for their claims to be processed. It is important to remember that when first introduced 13 years ago, direct provision was viewed as a time-limited system that would be for a maximum of six months. If this was the case, I would not be standing here today and I could tolerate the inadequacies that would present in that time period rather than the outright failings that present in this system, where the average length of stay is four years and a significant number have remained in the system for between five and ten years. This is far too long and leaves asylum seekers de-skilled, institutionalised, vulnerable to mental health issues and socially excluded.

The impact on children is particularly worrying. According to the Government’s special rapporteur on child protection, Dr. Geoffrey Shannon, “the specific vulnerability of children accommodated in the system of direct provision [is] the potential or actual harm which is being created by the particular circumstances of their residence, including the inability of parents to properly care for and protect their children and the damage that may be done by living for a lengthy period of time in an institutionalised setting which was not designed for long term residence”. The long-term solution has got to be a streamlined status determination system where decisions are taken fairly and speedily, with quick recognition of those identified as in need of refugee or subsidiary protection or leave to remain, or a speedy human rights compliant removal or deportation process. I hope this will be delivered through the Immigration, Residence and Protection Bill. I will make some recommendations when summing up the debate.

Minister for Justice and Equality, Alan Shatter TD

I thank the Senators who proposed the motion and all of those who have spoken on an issue of great importance in which I have had great personal interest for a considerable time. This important debate coincides with some events which have taken place over the past 48 hours in the State, which are not directly related to the direct provision issue but are related to the welfare of children.

I want to say to the House, and it is important I have an opportunity to say this, two children were removed from two families in the State in the past 48 hours in circumstances in which An Garda Síochána had serious concerns about the welfare of the children. Normally I would not address any specific cases which arise, and up to now when asked I have stated these are matters to be dealt with by the courts, but I want to report to the House the concerns which arose relating to the children have been proved to be groundless. I understand the two children concerned are children of the parents concerned and there is no reason for any doubts in this regard.

I am conscious An Garda Síochána has a very important role in dealing with child protection issues, particularly under the child care legislation of 1991 as amended, and circumstances do arise where for the protection of children it is necessary that An Garda Síochána intervenes and takes them to a safe place. I have no doubt the gardaí in this instance acted in good faith in the intervention which took place. However I have concerns with regard to each of these matters and I will ask the Garda Commissioner for a report on the background to each of these instances with a view to reviewing the procedures which applied in a manner which ensures An Garda Síochána continues to perform the very important role it must play for the protection of our children while also ensuring the type of situation which has arisen in each of these cases, which impacts on family members, mothers, fathers and children, can be avoided in so far as it is possible

I am conscious these events took place in a background or backdrop of events which have taken place outside the State, but it is very important in ensuring the welfare of all children is safeguarded and that every child in the State is afforded, where necessary, the protection of the State, that no group or minority community is singled out for unwarranted attention or suspicion with regard to child protection issues.

It is important that events which take place off this island in other states are not automatically assumed to be replicated in this State or in other states throughout Europe to the detriment of any particular group or minority being singled out. I am not suggesting this in any way was a motivation of the members of An Garda Síochána who in good faith acted in a manner they deemed appropriate in the interests of children, but it is important we do not get caught up in some of the concerns and the media spotlight which have arisen in the context of cases in other states about which there are genuine causes for concern. One case elsewhere, which is very high profile, is still a matter of investigation and a matter to be dealt with in the courts of another jurisdiction. I hope Senators will forgive me if I have taken this opportunity.

As I sat here, Members may have wondered why, on occasion, I was accessing my phone. It was not out of a discourtesy to anyone but because the results of certain tests were coming through to me and I was anxious to ensure I knew as soon as possible. The families concerned are being informed and, indeed, the court and the HSE are being informed. I believe these matters are sufficiently serious to warrant being mentioned in this House. I am conscious there is a very substantial interest in these matters outside this House, across the country and, indeed, elsewhere across Europe. It is important that the record on these matters be addressed.

I now want to return to the issue we are dealing with this evening and perhaps the House will give me some latitude by way of time to address these very important issues.

As I said earlier, I welcome this debate and the opportunity to respond to the points raised by Senators, and to speak, if I can, more generally about the subject in order to assist Members gain a fuller understanding of all the issues involved. At the outset, as Members will be aware, I have on several occasions in this House and in the other House responded to many, if not all, of the points referred to in this motion, and one of the earlier speakers referred to the number of times I have addressed this issue in this House. I am, of course, happy to address these issues again in the course of my contribution to this debate.

In saying this, it is important that I state that, for the avoidance of any doubt or misunderstanding and as has already been referred to, the issues under discussion here are currently being litigated through a judicial review application in the High Court, which essentially challenges the legal validity of the direct provision system. An application for leave for judicial review in that Mundeke case, so named after the applicants seeking the review, was formally heard in the High Court on Monday of this week, and the likelihood is that a full hearing of the case will take place early next year. I mention this with no purpose other than to ensure that all Members are aware of the most recent developments in this highly contested area of public policy. This can give rise to sharp differences of opinion among the wider community and, on occasion, is discussed in simplistic terms and in the colours of black and white when, unfortunately, in the complexities that arise, there are various shades of grey.

I do not know, and it may not be the case, whether this motion is being co-ordinated with developments in the case that is taking place in the courts as part of what is obviously an ongoing campaign against direct provision. Regardless, the House will understand that I cannot say anything here which will pre-empt the State’s response to the legal challenge that is taking place.

In the context of legal challenges generally, it is worth noting that a substantial number of those residing for long periods within the direct provision system are adults living with their children who have challenged in the courts, by way of the judicial review process, decisions made refusing applications for asylum and-or permission to remain in the State and whose cases await hearing or determination. There are presently approximately 1,000 such cases pending before the courts. Indeed, in many of the direct provision homes and accommodation I have visited, an overwhelming number of those being so accommodated, either themselves or their spouse, are engaged in litigation by way of judicial review, having been refused asylum. I believe that is an important statement to make. I am not challenging their right legally to bring judicial reviews but it is important to make the case clearly, as someone who comes from the perspective that, where someone is a genuine political refugee he or she should get refuge in this State, that there are many who claim to be political refugees who are not. I can say this having read the papers and seen the files.

These judicial reviews are taking place notwithstanding the existence of a detailed system of examination of asylum claims involving two bodies statutorily independent of the Minister, namely, the Office of the Refugee Applications Commissioner and the Refugee Appeals Tribunal. These bodies are to fulfil the State’s obligation to distinguish between genuine asylum seekers and economic migrants who have not obtained the appropriate visas for permission to remain in the State or work permits to obtain gainful employment.

I am aware that some of the strongest critics of the direct provision system outside of this House have said all that is required is “one last push” to have it brought down. They have been very slow to explain what they will replace it with. It is, of course, their right in our democratic system to take such an approach. However, in opposing the system of direct provision, which I have already freely admitted has many faults, I have yet to see any proposals, or at any rate, proposals grounded in the reality of the economic conditions we face, as to what could replace it without, in short order, recreating the crisis which led to its establishment in the first place. There is no gainsaying that truth, and anybody who believes otherwise is, at best, simply not prepared to face reality.

I listened with great interest to Senator Hayden telling me we should provide housing for practically everyone in direct provision and every future person who comes to the State seeking asylum. I do not know where I am to obtain the funding to do that. There is no reality in that. We have people born and living in this State who are currently in difficult financial circumstances but for whom the State cannot afford to provide housing because of the parlous financial circumstances of the State. We have to discuss these issues with a degree of realism. What would be the effect if we were providing a house for every applicant for asylum in the State? How many tens of thousands of people who are economic migrants would arrive in the State and say, “Hello. Could I have a house, please?”

Could we have some realism in this discussion? We must provide properly for those who are genuinely seeking political asylum, coming from some parts of this world where people are treated appallingly. However, let us not fall into the trap of believing that everyone who claims asylum is always, in all circumstances, telling the truth. Sadly, they are not.

The system of direct provision in this country is sui generis. There is no real comparator with any other form of accommodation being provided by the State. To understand the system, as well as its strengths and weaknesses, one has to take account of the circumstances which prevailed when it was first set up. The number of asylum applications in Ireland increased dramatically in the late 1990s. In 1998, some 4,426 asylum seekers applied for refugee status. In 1999, this figure rose to 7,724. On the basis of these trends, it was anticipated that between 12,000 and 15,000 would claim asylum in Ireland during 2000. At that time, the majority of asylum seekers arrived in Dublin, and still do, and the provision of accommodation for asylum seekers was handled, in the main, by the then Eastern Health Board, which treated the asylum seekers as homeless. In late 1999, the shortage of accommodation reached crisis point and the Eastern Health Board, understandably, could not cope. There were reports of asylum seeker families sleeping in parks because no accommodation was available for them. We have now forgotten that.

In November 1999, the Government decided to deal with the crisis by having the needs of asylum seekers met by a system of direct provision which also involved dispersal throughout the country. The Government’s decision was also made in the context of measures taken in other EU countries to control illegal immigration and to process large numbers of asylum applicants. The body set up under the auspices of my Department to carry out the Government policy was the Directorate of Asylum Support Services, DASS, which later became the Reception and Integration Agency, RIA. It was an important objective of the policy to ensure the availability of accommodation for all asylum applicants while their applications for asylum and leave to remain in the State were being processed and determined.

Since then, RIA policy has been to procure commercial properties such as hotels, hostels, boarding colleges and so on, from private operators through public advertisements seeking expressions of interest. This procurement policy is reflected in the current RIA portfolio. Of the 34 current centres, only seven are State-owned and, overall, only three are “system built”, that is, built specifically to accommodate asylum seekers. In terms of room capacities and facilities, RIA centres operate in compliance with relevant legislation. In regard to determining minimum room capacities, RIA relies on the Housing Act 1966, with particular reference to section 63 thereof dealing with the definition of overcrowding. In regard to shared bathroom and toilet requirements, RIA relies upon the Tourist Traffic Acts 1939 to 1998.

Where a family member, already in RIA accommodation, reaches ten years of age, RIA offers that family alternative accommodation which is deemed suitable for their needs.

In many cases, where the family profile has changed on the basis of age or a newly arrived family member, the Reception and Integration Agency can only offer alternative accommodation at another centre to keep within these rules. A family may, however, choose to refuse the offer of a transfer to an alternative centre because it prefers the current arrangement or wants to await a better offer. Where a family refuses an offer of alternative accommodation in such circumstances, the RIA keeps the family details under review and further offers are made as deemed suitable. The key point is that the Reception and Integration Agency must adapt existing premises for the purposes of accommodating asylum seekers. It is not realistic to expect bespoke accommodation for asylum seekers in accordance with what one may ideally wish to have in a centre.

In the current campaign against the system of direct provision there can be a tendency at times towards extreme claims which do little to help the residents involved. Regardless of how many times it is refuted, the canard continues to surface that asylum seekers in centres resort to suicide as a matter of course. Claims are also made that residents resort to prostitution in centres. Such claims have been investigated by the Garda in the past and found to have no basis. Any such allegation will continue to be investigated by the appropriate authorities in accordance with the law. Assertions about suicide, child abuse and prostitution among residents in asylum accommodation centres are still made by purported supporters of asylum seekers who would not dare to make such assertions in respect of any other identifiable group of persons in society.

While the direct provision system is not ideal, it facilitates the State in providing a roof over the heads of those seeking asylum or seeking to be allowed, on humanitarian grounds, to stay in the State. It allows the State to do this in a manner that facilitates resources being used economically in circumstances where it is under financial difficulty.

No Government can afford to ignore the likely consequences of a change to the system of direct provision. The system was examined in considerable detail in the 2010 value for money report which found there were no cheaper alternatives. If we were operating a system which facilitated asylum seekers in living independent lives in individual housing with social welfare support and payments, the cost to the Exchequer would be double what is currently paid under the direct provision system. I remind Senators that Ireland has still not exited the troika programme and even when we do, the State will next year spend €10 billion more than it receives through the many ways in which it obtains funding. If the State was to allow all asylum seekers to avail of full social welfare supports, including rent supplement, the immediate impact would be for all asylum seekers, including those not currently in accommodation provided by the Reception and Integration Agency, to avail of this financial support. As matters stand, not all asylum seekers live in direct provision accommodation as they are not compelled to do so. Accommodation is provided for those who cannot provide accommodation for themselves and do not have friends, family or others in the State who are willing to provide accommodation for them. Some asylum seekers live with friends or family or provide, from their own resources, for their accommodation needs.

A further concern is what is known across Europe as the “pull factor”. While the State has an important obligation to provide refuge for those in genuine need of protection and asylum and it is crucial that we comply with our international obligations in this regard, it is also appropriate to acknowledge that a significant number of those who have during the years sought asylum here have been economic migrants evading our immigration and visa requirements whose personal narratives have ultimately proved to be both untrue and unreliable. The State at this time cannot afford to provide supports and accommodation for individuals who so behave.

The decline in the number of those applying for asylum arriving in Ireland, from 11,600 in 2002 to 1,000 in 2012, is bucking the generally upward trend in the European Union. It must be borne in mind that the common travel area between Ireland and the United Kingdom, which for many decades has delivered immeasurable economic, social and cultural benefits, would possibly be abused by those using the asylum system simply to avail of better economic advantages in a context where Ireland provided better social supports and housing than are available in the United Kingdom.

No asylum seeker has ever been left homeless in the State. Unfortunately – it gives me no pleasure to say this – the same cannot be said by the public authorities responsible for homelessness issues among the indigenous population. Asylum seekers receive nourishment on a par with and, in some cases, superior to that available to the general population. They receive a health service on the same basis as Irish citizens and it is, in many cases, far superior to what is available in their countries of origin, rightly so. Children of asylum seekers are provided with primary and secondary education in the local community on the same basis as the children of Irish citizens.

The direct provision system remains a key pillar of the State’s asylum and immigration system and I have no plans to end it at this time. I accept, however, that the length of time spent in direct provision accommodation and the complexity of the asylum process are issues that need to be addressed. I have visited a number of asylum accommodation centres, most recently last Friday when I visited the Ashbourne centre in Glounthane, County Cork. I am concerned at how long people spend in the system. My resolve, therefore, is to deal with the factors which lead to delays in the processing of cases in order that asylum seekers spend as little time as is necessary in that accommodation system.

As with other states, Ireland has individuals and families who apply for asylum and have genuine grounds for seeking asylum under the relevant international provisions in place and our domestic laws. Of those granted citizenship in the ceremonies in which I was engaged on Monday last in the convention centre in Dublin, 195 were political refugees. A substantial number of people who are economic migrants present with stories seeking asylum which turn out to lack validity. There are individuals who adopt false identities and pretend to come from troubled parts of the world when they do not. There are also individuals who will claim to have been in war zones and when the matter is further investigated, it transpires they were in London, Birmingham or elsewhere when they alleged they were in Sudan, Somalia or some other troubled region. This is a real problem in dealing with the asylum system. Many also play the system by instituting one legal challenge after another to delay the inevitable, sometimes to the point of launching legal challenges as they are about to board an aircraft to be returned home. That is their right, but we should not lose sight of the fact that the right of easy access to the courts in this respect is almost without equal in the world.

There is a need to bring balance to the discussion on asylum seekers. In the context of the wider community and those campaigning, there is an assumption that every single individual who applies to seek asylum is giving a truthful account of his or her circumstances and is a genuine asylum seeker. On the other side of the debate, there are small numbers of individuals who doubt whether any applicant for asylum ever tells the truth. We must adopt a balanced approach and ensure no individual who truthfully documents events or circumstances in respect of which asylum should be granted is refused the protection he or she seeks, while also ensuring those who deliberately abuse the asylum process to evade our immigration laws do not benefit or, by their conduct, undermine our asylum system and the basic humanity it is right to afford to those in need of protection. We must ensure the integrity of the asylum and immigration system is upheld in order that assistance is afforded to those who genuinely seek asylum, while not allowing the system to be undermined by those seeking unfair advantage.

Having made these general points about the direct provision system, let me deal with the various points raised in the motion, the first being the view of the Government’s Special Rapporteur on Child Protection, Dr. Geoffrey Shannon, in his fifth report in July 2012 that the system should be examined with a view to establishing whether it is detrimental to the welfare and development of children and, if appropriate, an alternative form of support and accommodation should be adopted which is more suitable for families, particularly children. The Reception and Integration Agency affords the highest priority to the safeguarding and protection of children through the full implementation of the Children First guidelines. It has a fully staffed child and family services unit, the head of which is seconded from the Health Service Executive. Any review of the type proposed would have to take account of the wider purpose of thedirect provision system in the overall context of the State’s response to the issue of asylum seekers and immigration control generally.

The accommodation system cannot be in place solely in its own context. It is inextricably linked with the surrounding international protection process. An amended immigration, residence and protection Bill will be published, the purpose of which will be to substantially simplify and streamline the existing arrangements for asylum, subsidiary protection and leave to remain applications. It will do this by making provision for the establishment of a single application procedure in order that applicants can be provided with a final decision on all aspects of their protection application in a more straightforward and timely fashion. I had wished to bring forward this legislation much sooner. It has been one of my great frustrations that it has not yet proved possible to publish the legislation in its final form.

However, as Members will be aware, by necessity, troika-related legislative requirements have had to trump all other proposals, no matter how meritorious. The available pool of legislative drafting expertise is quite small and is subject to the same resource restrictions as all other areas of the public service. However, I expect that this situation will be alleviated shortly and that the Bill will definitely come before the Oireachtas next year. It was originally my hope to have seen it in 2012 but that proved impossible. Everything possible is being done on the legislative drafting side to bring about publication by 2014.

In relation to the establishment of an independent complaints mechanism through the Ombudsman for Children and independent inspections of direct provision centres undertaken through HIQA, it is not clear from the rapporteur’s report that he was aware of how these issues are actually dealt with. I see no basis for HIQA involvement. Reception and Integration Agency, RIA, centres are already subject to inspections three times a year, twice by Department of Justice and Equality staff and once by an independent company called QTS. Indeed, the media reports last week about shortcomings in some RIA centres came about from the release under FOI of inspection reports carried out by RIA which showed that the inspection system was indeed working. Where problems within direct provisionaccommodation are identified, I ensure that these are addressed. RIA will publish on its website all completed inspection reports on its centres undertaken since 1 October 2013. In future, anyone seeking these reports will not have to make any application under freedom of information legislation. I want these reports to have maximum transparency.

Although not stated explicitly in the report, the rapporteur appeared to be making an analogy with the HIQA inspections of children’s detention centres but there are several distinctions to be drawn. Senator van Turnhout had some difficulty with some of these distinctions but they are valid distinctions. First, only a small number of children are at present in detention while approximately 1,200 children are in the 34 RIA centres around the country. Second, HIQA carries out the inspections on a contract basis for the Department of Children and Youth Affairs, and not under the specific HIQA legislation. The inspections are based on the standards drawn up by the Department of Children and Youth Affairs, not by HIQA. Third, the inspection standard of the Department of Children and Youth Affairs takes into account that these children are in the care of the State, that the State acts inloco parentis, in the context, in most cases, of proceedings having been taken in respect of child care matters. While the RIA has, of course, a duty of care to all its residents, both adults and children, in no case is it acting in loco parentisin respect of children in the centres.

On the recommendation to extend the remit of the Ombudsman for Children to direct provision centres, I see no basis for changing the law in this regard. Section 11(1)(e) of the Ombudsman for Children Act 2002, provides that the ombudsman shall not investigate any action taken by a public body where the action was taken in the administration of the law relating to, inter alia, asylum. While the office currently does not have the power to investigate asylum-related matters, the Irish Naturalisation and Immigration Service, INS, including RIA, has administrative arrangements in place with the office to assist and provide information and to help resolve any matters brought to its attention. The rapporteur’s report also does not make clear that the ombudsman does not serve as a first instance appellant authority for day-to-day administrative complaints mechanisms. It is a requirement that a person who wishes to appeal to the ombudsman must first try to solve the problem with the public body concerned using formal local appeals mechanism.

With regard to the legislative basis for payments to asylum-seekers in direct provision accommodation, asylum-seekers cannot work under section 9(4)(b) of the Refugee Act 1996, they cannot access rent allowance under section 13 of the Social Welfare (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 2003, nor are they entitled to a range of benefits, including child benefit, as they are deemed to be not habitually resident under section 246(7) of the Social Welfare Consolidation Act 2005.

The Minister for Social Protection has already responded to Dáil questions on this matter, to the effect that under thedirect provision system asylum-seekers are provided with full board accommodation and other facilities such as laundry services and access to leisure areas. To take account of the services provided, a direct provision allowance of €19.10 per adult per week and €9.60 per child per week is payable in respect of any personal requisites required. Following the introduction of the statutory habitual residence condition in May 2004 and subsequent legislation, asylum-seekers are not entitled to receive most social welfare payments. The payment of the weekly direct provisionallowance is made on an administrative basis by the Department of Social Protection on behalf of my Department. It continues to be open to any asylum seeker to seek assistance for a particular once-off need by way of an exceptional needs payment under the supplementary welfare allowance scheme as contained in section 201 of the Social Welfare Consolidation Act 2005. There is no automatic entitlement to an exceptional needs payment as each application is determined based on the particular circumstances of the case.

With regard to the final issue raised concerning a debate with Members of Seanad Éireann as to how to best reform Ireland’s reception and asylum system, only someone unfamiliar with parliamentary affairs would think that there has been little or no debate about the merits or otherwise of the direct provision system. I have answered over 50 parliamentary questions on the topic this year, as well as five Seanad Adjournment debates, not including this one. RIA has facilitated three visits by Members to asylum accommodation centres. Senators are welcome to visit any further centres they wish to visit. It is one of my practices as I travel around the country and without media attention to quietly visit our prisons and our courts and to meet with members of An Garda Síochána. Quietly and without any great fanfare I have visited a number of our asylum-seeker accommodation centres and met and talked to many of the people residing therein. I intend to continue this practice. In its previous iterations, the Immigration, Residence and Protection Bill has been extensively debated in the Oireachtas and no doubt will be debated again when finally I can introduce the new Bill which we hope to publish.

I wish this were an issue with an easy resolution but this is not the case. It is a challenge, not just for Ireland but for the EU as a whole and the issue is discussed at practically every Justice and Home Affairs Council meeting at the various locations. The direct provision system is a necessary feature of this country’s asylum and immigration system. It is a system which ensures a roof over the head of every asylum-seeker. However, I would prefer to have a system where asylum seekers spend less time in that system. That is where my energies will be devoted. I want to see the new Bill published. I want us to get to a position, which we have not as yet achieved, where all the applications made by those seeking asylum, including all the different applications that can be made, are dealt with in one application. I want to have an appeals system which is to the satisfaction of everyone so that in the future, those seeking asylum do not feel the need to make multiple applications to the courts.

In conclusion, after we have enacted our legislation, which I hope will meet with a widespread welcome, which will ensure that we are fully meeting all our international obligations and which will address issues of concern to some, I will then revisit the possibility of our becoming parties to some of the EU measures to which Senators have referred. There is merit in looking at a system which ensures that we treat those who are genuine asylum-seekers as best we can, with the caveat that in all contributions on this issue, I urge Senators to take note of what I have said that many people are genuinely seeking asylum but, unfortunately, others are economic migrants masquerading as asylum-seekers. This is a problem right across Europe. We live in a State that does not have an open-ended fund into which we can simply dip to provide ideal accommodation and supports for everyone who arrives at our borders. We cannot provide the ideal within the current economic climate for all of our citizens. There are limits to what we can do. We need to take a reality check when debating this issue.

I am very conscious, in the context of those who are currently within the direct provision system, as well as those still involved in the process but living with friends, relations or in their own accommodation, of the welfare of children resident in this State for many years. It is an issue that will have my continuing attention, and Senators should notice that the number of people currently in direct provision is a smaller than it was on 9 March 2011.

I will first deal with the Minister’s statement on the events of the past 48 hours. I thank him for his honesty in sharing his concerns and the plans for the proposed review. I agree the Garda Síochána has an important role to play as part of the child protection system. Nevertheless, I am concerned about the amount of detail that went into the public domain with these cases, and I support the Minister’s proposal for a review.

I have plenty of food for thought arising from this evening’s debate and I thank all colleagues for the contributions. I assure the Minister I am fully aware of the separation of powers, and the motion today is a culmination of my work as a Senator and that of my colleagues. Senator Moran raised the 2010 value-for-money report, which clearly indicates that the social welfare option costs are the same as direct provision, so I am finding it quite difficult that we are being played against each other. Examining the current funding of some providers, it seems many have moved to unlimited companies to hide profits. I would happily sit down with colleagues to work on an alternative model that would be based on human rights and be economically sound, if we felt it would get a fair hearing.

I have been careful with my wording on this issue and I am disappointed at the response. I wanted to have a constructive debate; instead the Minister’s response has added bricks to the wall. I do not want to table Adjournment debates and use up departmental time going back and forth. I would like to sit down to talk about how we reform this system. I do not want to ask questions about this case or that case. That is why I worded the motion as I did. Along with my colleagues, civil society organisations, legal practitioners, academics, human rights activists, I am calling for reform. I am sure Senators would be happy to co-ordinate with a grouping to sit down to talk about the solutions if we believe they will get a fair hearing.

The Minister mentioned Dr. Geoffrey Shannon’s report. Why not ask him to conduct the examination he proposed in his special rapporteur report if he is so assured of the facts? There is merit in doing a report on the effects of direct provision on the welfare and development of children.

I worked to have a constructive debate but I feel like I have had a few wallops. The Minister said “No” to any independent mechanism and to investigating conditions for children and he refuted the economic arguments, even though the value for money report defends what we said. There has to be a better way for us to reform policy. We are here together and we want to work with the Department. I read what the Minister said when he was in opposition. His comments were much stronger than mine during this debate. Why can we not find a way to sit down to reform this system? The difficulty when it is all boiled down that is my colleagues and I can put faces to the many figures that have been provided in this debate. I realise what we are doing and I do not want in ten years’ time to stand anywhere and say, “Well, we knew that was happening but we did nothing”. We have to do something.

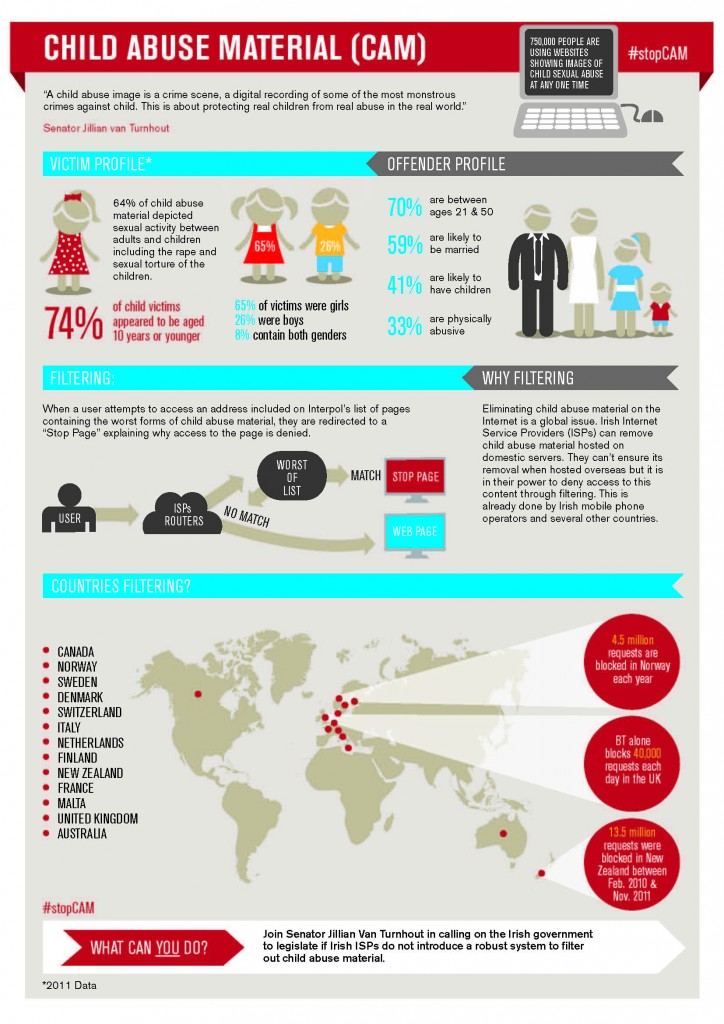

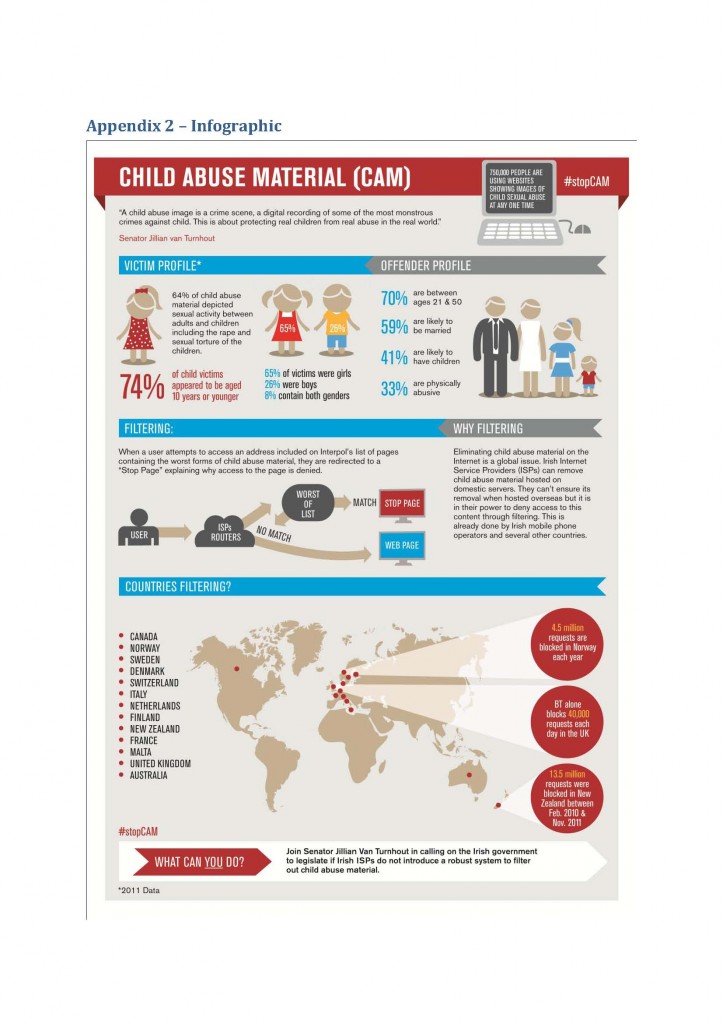

Online CAM Infographic

Report on Effective Strategies to Tackle Online Child Abuse Material

The Politics of Direct Provision

My entry point into the issue of direct provision is from a children’s rights perspective. This perspective has been informed by my work on related issues as the former Chief Executive of the Children’s Rights Alliance; the recommendations of the Government appointed Special Rapporteur on Child Protection, Dr Geoffrey Shannon; the concerns raised by advocacy groups; and my own recent visits to two direct provision asylum accommodation centres as an independent member of Seanad Éireann.

It has taken me a long time to wade through the mire that is the political discourse on direct provision. It has been difficult to establish which features of the system belong to the remit of the Department of Justice and Equality, the Department of Children and Youth Affairs or indeed the Department of Social Protection. I have struggled to understand the distinction drawn between children “cared for by the State”, as is used to describe children in direct provision, and children “in the care of the State”. I have argued strenuously that firstly, children are children irrespective of status and secondly, that it is a stretch in credulity to claim that children in direct provision are in the care of their parents in circumstances where the parents’ autonomy to make even basic decisions about their children’s care, for example what and when to eat, is so limited as to render it absent.

My overwhelming concern is that the administrative system of direct provision, which has been operating in Ireland since April 2000, is detrimental to the welfare and development of asylum seekers, and in particular the 1,808 children currently residing in direct provision accommodation centres throughout Ireland . There are a plethora of difficulties, many of which I have raised under Adjournments of the Seanad including: the dubious legality of the direct provision system; the lack of an independent complaints mechanism for residents; the absence of independent inspections of direct provision centres where children reside; the decision by Ireland to opt-out of the EU Directive to allow asylum seekers to enter the work force if their application has not been processed after one year; the fact that there are no prospects for post-secondary education for young asylum seekers, which is like hitting a pause button for an uncertain and doubtlessly lengthy period of time; the fettering and erosion of normal family dynamics and functioning; and the lack of autonomous decision making.